When I was a boy, my father would often take me to the movies at a Milwaukee landmark called the Oriental Theater, which would play classics and from time to time stage rock shows. It’s where we saw Gone with the Wind and Citizen Kane; every Marx Brothers film and old reruns of Sid Caeser’s Show of Shows; Black Orpheus, the films of Truffaut, Renoir, and of course, everything made by Mel Brooks. As a teenager I saw Devo and the Talking Heads there and once even rescued a friend from a date gone wrong at the Rocky Horror Picture Show.

The Oriental Theater, we might say, was an institution that had an idea of itself. It knew who it was, who it wanted to be, and, was confident that in its commitment to art, others could eventually find themselves as well.

Like many fathers of his generation, my dad would never leave the theater until the lights went up because the rolling credits were like a walk of Jewish pride. Writers, directors, producers, actors, camera operators, gaffes, you name it — names and positions would roll by and my dad would point out the Jews. His pride was a given: he didn’t have to name it. Son of a refugee; veteran of the Second World War; a college degree thanks to the GI Bill; he was grateful for all America had given him and he was damn sure going to celebrate the achievements of other Jews as well. In other words, like the movie theater’s credo, artists were at the front lines of an innate human mandate to be oneself. To join the unique one to the whole to make a greater whole. Like that great American phrase, “from many, one.”

With the inevitable independence of young adulthood, having experienced a less sanguine view of American patriotism growing up amidst the wrenching debates and violence of the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, US military involvement with dictatorships in Central and South America and an escalating Cold War with the Soviet Union, I was more mixed about serving our country when President Reagan required registration for the Selective Service of those students eligible for student loans. My friend Allen and I — both opposed to registration — sat across from our dads one afternoon and debated the merits of our views. Both men had fought for America to defeat fascism and were not particularly interested in our view of just and unjust wars. They felt, plain and simple, that national service was a duty of all Americans and that if we opposed where we were being sent, we had ways of communicating, talking to others about it, but nothing would replace the overriding obligation to serve.

The dads won the debate. We registered. In protest, I suppose, but signed up we did though there never was a draft. Perhaps Reagan was playing to a voting bloc, perhaps he was genuinely convinced of the merits of readiness during a Cold War that showed few signs of ending. We’ll have to go back to the archives for that.

But the concession to civic obligation despite objection is a lesson I have carried with me throughout a lifetime of service, albeit Jewish service, since our nation in fact asks very little of us. We require nothing of our youth when they turn eighteen; we don’t like to pay taxes; our infrastructure is in disrepair; the gap between rich and poor is unconscionably wide; and still, more than four hundred years since slavery was introduced to North America, we have yet to adequately address the great injustice that lies at the center of the American project.

No requirement of duty beyond the self? Come on: there is so much work to do. I refuse to believe that self-service is a runaway train and that we are witnessing the end of America as we once knew it. Rather, I take the view, especially in light of violent, racist and anti-Semitic mob attacks in the nation’s Capitol this past week, that we are finally seeing a long overdue reckoning for a new spirit and a new patriotism to begin to emerge. We are not there yet; not even close.

But if you’re like me and you listen to the voices of young people, behold their diversity, their openness to questions of race, gender, class and identity, you can’t help but think that the toxic mob of hate that polluted Washington this past week is in fact a cancerous burst of exhaust sputtering from the beat-up jalopy of a nation that is transforming itself before our very eyes.

Watching in horror while neo-Nazis and white supremacists desecrate the corridors of democracy this week might have you thinking otherwise but don’t take the bait. Don’t give in to despair. Don’t believe everything you see. You must play the long game. Or, as they say in the Black civil rights movement over and over and over again: Keep your eyes on the prize. Wade in the water. The arc of history is long and it bends toward justice.

For all of us suffused in the often fetid pools of social media and the immediacy of communication, feral neurological gratification from seeing a chat or tweet or tik-tok click-clack its way into your soul, remember this: principles like Freedom, Justice, Equality and Liberty are won not in an instant; nor in a lifetime; but in several lifetimes, in an accumulation of efforts over generations of time. Ours is to play the part in our time. Or as Woody Guthrie once said, “Whose side are you on?”

You can probably guess how I feel about the degrading narcissism of our nation’s president enabling and encouraging the violence and malignancy of American bigots. You can probably guess how I feel about the countless others who enabled him for their own reasons, their own agendas, these last many years. And I, as an American and as a Jew, with a conscience shaped by the kilns of history and human suffering, not only refuse to give in but am in fact energized, even more now, to win the day not just for myself but for all Americans, believers and non-believers, from every imaginable race and gender and economic station in life. Why? Because Freedom and Justice and Equality are all expressions of the particularity of what God has designed for us as it is written in our holiest books and because being free and equal among those with whom we share community, wherever that community is, seems like a pretty damn good way to live.

True story. In 1969, before Bud Selig brought the Brewers to Milwaukee, the Chicago White Sox used to play games at County Stadium. My dad and uncle took me and my cousin Mike to see a game on a warm summer night. Some raucous fans were pounding beers in front of us and my dad said to them, “Hey, could you keep it down?” One miscreant said, “Shut up, kike.” And without a moment’s notice, my Uncle Bill, who had been a Big Ten champion boxer at UW-Madison in the fifties, punched the guy’s lights out with one blow.

He deserved it. We left. And in the parking lot on the way to our car, I asked my dad, “What’s a kike?” His answer has stayed with me like every lesson he gave me: “It’s a Jew, son, in the mouths of people who hate us.”

If you’re like me, you wanted to throw some punches this week, too.

*****

“A new king arose over Egypt who did not know Joseph. And he said to his people, ‘Look, the Israelite people are much too numerous for us. Let us deal shrewdly with them, so that they may not increase; otherwise, in the event of war they may join our enemies in fighting against us and rise from the ground” (Exodus 8-10).

Sound familiar? It should. It is the root text of anti-Semitism. It is the view that the Jew is an outsider, not able to be trusted, disloyal, conniving, abundant. It is also the playbook that American racists from Father Coughlin to Strom Thurmond to George Wallace to Donald Trump have deployed. The Exodus story, which in its fundamental composition is the story of a minority people, consigned to the status of “other,” is singled out, oppressed, persecuted and enslaved so that the “true nation” may thrive. Arguably, we Jews have experienced this on a scale unlike any nation on earth. Yet, with our Torah’s commandment that each of us is made in the “divine image” and that we are to “love thy neighbor as thyself,” there is also an undeniable universalism to our particular message of what God expects of us.

We are inextricably bound to one another; each of us are children of God; or, as the coin of the realm proudly proclaims, “e pluribus unum — from many, one.”

Do you find me rambling? I may be. After all, I am as heartbroken and shocked and angry as you are right now. But as your rabbi, it is my obligation to offer you words of hope, perspective, and comfort, in the face of one of the ugliest displays of hatred and violence wrought by an American president in the history of our nation.

Will there be justice in the weeks and months ahead? I hope so. Will a new administration encourage cooperation, openness, patience and understanding in the weeks and months ahead? I hope so. Will the ever-changing face of America continue to grow and evolve, yielding new definitions, new possibilities, and a new way forward for all Americans? I won’t quit until it is so. And neither should you.

*****

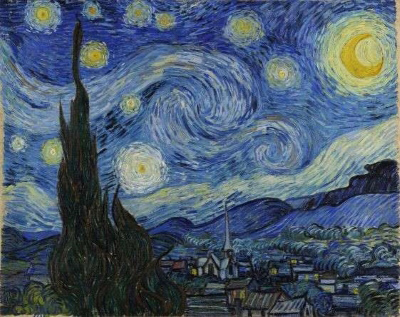

Two images hang above my dresser. I look at them each day as I prepare to face the world.

One is a cross-stitch made by my mother in 1964 when I was a year old. John F. Kennedy had been killed; President LBJ had deepened American involvement in Vietnam; after the shedding of much blood, after the deaths of too many for the right to vote, including James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, the United States Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which banned segregation in public places. Aquaint piece of Americana says, “My country tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of theeI sing.” Of course, my mother meant this all quite sincerely. She was hardly nodding to George and Ira Gershwin, George S. Kauffman and Morrie Ryskind’s satirical American musical about politics in the 1920s and 1930s but there is a connection here.

Because we Jews, as we always have, embrace our patriotism and critique it; we are proud and ashamed; we know what we know but want to always know more, do more, and in doing so create a better iteration of the American project on America. What did Rabbi Tarfon say? “You are not obliged to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

I can get behind that. Can you?

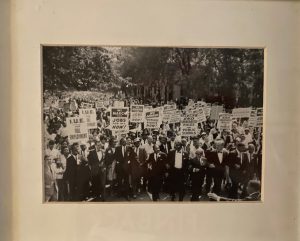

The other image is a photograph of Rabbi Joachim Prinz and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. walking together at the 1963 March on Washington. Rabbi Prinz, a Berlin refugee from Nazi Germany who would speak at the rally; and Rev. Dr. King, who would soon be martyred for his Biblically mandated insistence that equality is a divine right.

That day in Washington, between the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson and Reverend King, Rabbi Prinz said:

“America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent. Not merely black America, but all of America. It must speak up and act, from the President down to the humblest of us, and not for the sake of the Negro, not for the sake of the black community but for the sake of the image, the idea and the aspiration of America itself.

Our children, yours and mine in every school across the land, each morning pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States and to the republic for which it stands. They, the children, speak fervently and innocently of this land as the land of ‘liberty and justice for all.’

The time, I believe, has come to work together — for it is not enough to hope together, and it is not enough to pray together, to work together that this children’s oath, pronounced every morning from Maine to California, from North to South, may become a glorious, unshakeable reality in a morally renewed and united America.”

Moments later, as he concluded his iconic and monumental “I Have a Dream” speech, Dr. King said:

“This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with a new meaning,

‘My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.’

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California!

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee!

Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual,

‘Free at last! free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

Our Torah portion this week begins with slavery. But we know that it ends with freedom. And our week this week began with an abhorrent desecration of our nation’s most revered institution; but we must have faith in its restoration, its potential for integrity; and its facility as a tool for liberty and justice for all.

Keep the faith, friends. Fight the fight. Love thy neighbor as thyself. These are challenging times but we have seen darker ones. We will make it through with faith, hope, hard, hard work, and love.